This news article was originally published on the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory website.

Preparing for Volcanic Eruptions at Okmok Volcano, Alaska

Researchers are working at a remote ranch in the Aleutians, commuting by helicopter to the brim of a volcano to perform maintenance on their monitoring equipment.

By Einat Lev

October 3, 2022

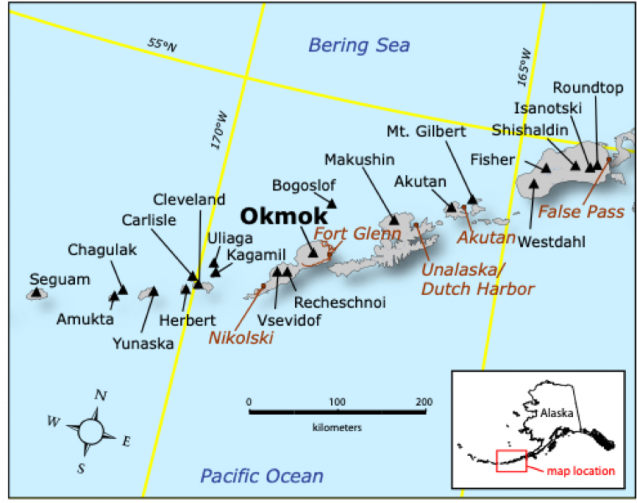

Location of Okmok volcano in the central Aleutian Islands, which form an arc connecting western Alaska with Northern Asia. Other volcanoes, including Cleveland, are marked by black triangles, and local communities are shown. Inset map shows context with respect to Alaska. Map: Larsen et al., 2015

Okmok volcano off the coast of Alaska has been continuously inflating since its last eruption in 2008, telling us that new magma is probably accumulating under it and that the next eruption is not far in the future. We therefore chose it as a primary target for our project, Anticipating Volcanic Eruptions in Real-Time (AVERT). AVERT is a collaboration between Columbia University and the Alaska Volcano Observatory to study volcanoes in Alaska using a wide variety of monitoring instruments and modern technologies—including high-accuracy GPS position tracking, magnetometers, infrared and visible webcams, and fast satellite communication. This new network is designed to provide real-time data directly from the volcano that will be immediately open to scientists and the public to use.

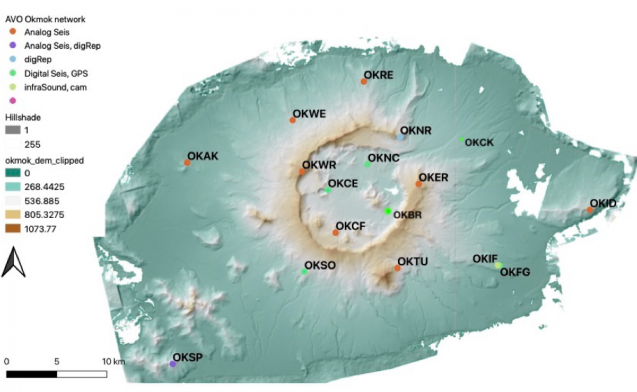

A map showing the topography of Okmok volcano, showing its central caldera and the cones within it. Four-letter acronyms starting with OK mark the locations of monitoring stations. This year's goal is to add GPS, magnetometer and satellite data transmission to OKAK and OKWE, GPS and magnetometer to OKBR and OKCF, and many fixes and updates at multiple other stations.

After delays due to COVID and poor weather, we finally made it to Okmok in mid-September. The journey here was by no means short or easy — some of us arrived here after spending three weeks on a research vessel at the neighboring volcano, called Cleveland on the Island of Four Mountains, which is also a part of the AVERT project. Others traveled from New York to Anchorage, then took a small plane to Dutch Harbor, then boarded a small boat for a 9-hour-long trip from Unalaska Island across to Unmak Island, where Okmok is located. We also brought with us a lot of equipment, including tens of batteries, solar panels, sensors, and, of course, lots and lots of food.

Loading our food and equipment on the Miss Alyssa at Dutch Harbor. Photo: Einat Lev

Our food and equipment inside the Miss Alyssa. Photo: Einat Lev

After unloading all the gear and food at the dock, we transferred it to the place that is going to be our home for the next two weeks: the Bering Pacific Ranch on Umnak Island. Located on a former WWII-era military base, the ranch used to have thousands of cattle heads, many of which still roam the land freely. We tried our best not to bother the bulls.

A typical view on the Bering Pacific Ranch. Rusted machinery from bygone eras, cattle roaming freely, and Ship Rock, a prominent rock feature in the sound between Unalaska and Umnak. Unalaska is visible in the background. Photo: Einat Lev

Looking west from the Bering Pacific Ranch towards Tulik, an older volcanic cone on the southern flank of Okmok. The snow-covered southern rim of the Okmok caldera is visible in the background. Working in the Aleutians in September means colder temperatures but also less fog. Photo: Einat Lev

Our only means of transportation between the ranch and the monitoring stations is a helicopter, which makes for a fun adventure! But it also means we are very sensitive to the weather conditions and can't go out if it is too windy or cloudy where we are trying to get to. Transporting by helicopter also allows us to collect many aerial photos, which we use to create detailed 3D models of the volcanic cones and flows. These will reveal information about the rates at which the landscape is evolving over time.

Our helicopter and a full rainbow. Continuously changing weather conditions alternating between rain and sun make for many beautiful rainbows. The cabin is the same one as in the previous photo. Photo: Einat Lev

Our helicopter against the conical silhouette of Tulik during sunset. Photo: Einat Lev

Our team unloading from the helicopter one evening on the ranch. Photo: Einat Lev

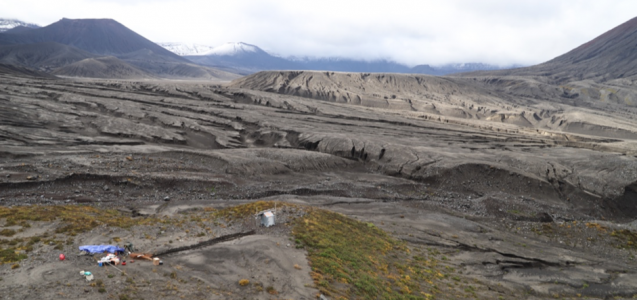

The scenery at our stations and en route between them is spectacular. For example, the way to the sites within the caldera usually takes us through a narrow opening in the rim nicknamed “The Gates.” A river with big waterfalls flows through The Gates, making the entrance breathtaking every time — and not only because of the bumpiness due to the always-windy conditions. Stations within the caldera have views of the multiple volcanic cones and flows, while stations outside have views of the ocean and the caldera rim.

Big waterfalls on the river that drains the Okmok caldera through The Gates. Photo: Einat Lev

The Gates, looking towards the Okmok caldera. Photo: Einat Lev

Field tech Cora Siebert from Alaska Volcano Observatory installing a radio antenna at site OKNO, with the north rim of the caldera behind her.

On a clear day, Station OKBR, located inside the caldera on the south side, has a view of four different volcanic cones. Photo: Einat Lev

Cows are not the only animals we meet on the island. The island has many caribou living on it, several foxes frequent the ranch house hoping for scraps, bald eagles fly above, and there is even a small herd of wild horses.

Wild horses in the pasture by the shore, with snow-capped Tulik and the Okmok caldera rim in the background. Photo: Einat Lev